Audit of Political Engagement 15

After four major electoral events in four years, some political engagement measures have been boosted to their highest levels in the 15-Audit series. Our 15th Audit of Political Engagement (2018) also shows public dissatisfaction with political parties and the system of governing, and a stark digital divide in levels of online engagement.

Executive summary

Electoral events over the last few years may have acted as ‘electric shock therapy’ for political engagement. Compared to the first Audit in 2004, people’s certainty to vote and interest in and knowledge of politics are all higher, but their sense of political satisfaction and efficacy have declined

- The share of the public saying they are certain to vote is at a new Audit high of 62%, 11 points higher than in the first Audit in 2004. The number saying they are interested in politics is seven points higher than in Audit 1 (57% vs 50%), knowledgeable about politics 10 points higher (52% vs 42%), and knowledgeable about Parliament 16 points higher (49% vs 33%).

- But, compared to 2004, satisfaction with the system of governing Britain is down seven points (36% to 29%), and people’s sense of being able to bring about political change (our efficacy measure) is down three points (37% to 34%).

Public engagement has generally improved in the year immediately after every general election. 2018 repeats this pattern

- Compared to last year, certainty to vote is up three points to 62%, interest in politics four points to 57%, self-assessed knowledge of politics three points to 52%, knowledge of Parliament four points to 49%, and the number of people who have undertaken a political activity in the last year six points to 75%.

- 27% feel they have influence locally, up four points from last year. This is the highest score for this indicator in the Audit series.

- This year saw some notable rises in political engagement among some traditionally less engaged groups, namely those in social class DE, BME respondents and women.

Youth engagement has risen but only in line with the population overall: a tremor, not a quake

- Among 18-24s, certainty to vote rose five points from last year to 44%, the highest in the Audit series. Compared to Audit 1 in 2004, it is 16 points higher.

- 18-24s’ knowledge of politics is also up since Audit 1 in 2004, by eleven points (28% to 39%), as is their interest in politics (by six points, 35% to 41%) and their sense of political efficacy (also by six points, 35% to 41%).

- However, like the population overall, 18-24s are less satisfied with the system of governing Britain than they were at the start of the Audit series. 18-24s’ satisfaction with the system of governing Britain has deteriorated by seven points since Audit 1 in 2004 (35% to 28%).

In Scotland, political engagement is mostly higher compared to 2004, but the post-independence-referendum upsurge has not been sustained, and political dissatisfaction is high

- Only 14% of Scots say they are satisfied with the system of governing Britain, a decline of three points in a year and 22 points since the first Audit in 2004.

- Compared to last year, interest in and self-assessed knowledge of politics are both up four points, to 62% and 56% respectively. But certainty to vote dropped 10 points, to 59%, below the Britain-wide average.

- Compared to Audit 1 in 2004, certainty to vote is up five points, political interest 16 points and knowledge 25 points. But people’s sense of political efficacy is down nine points at 36%.

Support for the greater use of referendums has declined again

- Overall support for the greater use of referendums stands at 58%, down three points in the last year.

- Before the EU referendum (Audit 13 in 2016), this stood at 76%.

Barely more than two in 10 people think the system of governing Britain is good at performing any of its key functions, apart from protecting the rights of minority groups

- Overall, 31% think the system of governing is good at protecting minority rights. However, BME respondents are more likely than white respondents to think it is bad at doing this (40% compared to 31%).

- For other functions, the numbers of people saying the system performs well are just 26% for ‘providing political parties that offer clear alternatives to each other’, 22% for ‘providing a stable government’ and ‘ensuring the views of most Britons are represented’, and 21% for ‘allowing ordinary people to get involved with politics’. The system is seen to be worst at ‘encouraging governments to take long-term decisions’: 17% think it does this.

In people’s party choice, trust matters most, followed by policies and representation, with competence some way behind, but most people think political parties are just ineffective

- As the most important factor in determining their vote, 32% said whether a party ‘can be trusted to keep its promises’, 30% that it ‘has policies I fully support’, 28% that it ‘represents the interests of people like me’ and 20% whether it ‘is the most competent’.

- Among the functions of political parties, people rate parties most poorly for their capacity to provide a way for ordinary people to get involved with politics; just 16% think they are good at this.

- Of ‘leave’ voters, 48% think political parties are bad at telling voters about the issues they feel are most important to Britain and how they will work to solve them, against 36% of ‘remainers’ saying the same.

- 50% say they were happy with the choice of political parties available to them at the June 2017 general election, 29% that there was more than one party that appealed to them at that election, and 37% that they are a strong supporter of a party.

Among different sources of news and information respondents used to inform their decision-making at the 2017 general election, party leaders’ debates and political interviews were the most important

- 74% of those who used them said the party leaders’ debates and political interviews were at least ‘fairly important’ in their decision-making, and 72% that they were influenced by face-to-face discussions or conversations with other people.

- 49% were aware of parties’ printed campaign publicity, but just 34% of them said it was important in deciding whether and for whom to vote, the lowest score for any of the sources of election news and information tested.

Digital and online are still far from overtaking traditional sources of information, but sharp digital divides suggest our future democracy will be shaped by the tools used by the youngest

- News or news programmes on TV or radio were the leading source of election-related news or information at the 2017 general election: at 69%, they had a reach 20 points beyond any other source.

- 48% of the public report having undertaken no form of online political engagement in the last year.

- Age divides are stark: watching politically-related videos online was done by 43% of 18-34s but 15% of over-55s; visiting the social media account of a politician or political party by 29% of 18-34s but 12% of over-55s; sharing something politically-related online by 21% of 18-34s but 11% of over-55s.

- 55% think social media help broaden political debate by giving a voice to people who would not normally take part, and 40% that social media help break down barriers between voters and politicians and political parties.

- But 49% think social media are making political debate more divisive, and 46% that it is making political debate more superficial.

Enjoy reading this? Please consider sharing it

Latest

Compendium of Legislative Standards for Delegating Powers in Primary Legislation

The scope and design of the delegation of legislative powers in any Bill affects the long-term balance of power between…Parliament and Government. The House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC) scrutinises all such delegation. This report distils standards for the delegation of powers from 101 DPRRC reports from 2017 to 2021.

Genetically modified organisms: Primary or delegated legislation?

A Statutory Instrument comes into force on 11 April that changes the legal requirements for the release of certain types… of genetically modified plants. Some argue that the changes should have been made by primary, rather than delegated, legislation. Where does the boundary between the two lie?

Constitution and Governance in the UK: Parliament and Legislation

The Brexit process, the pandemic and the approach of the Johnson Government have all tended towards Parliament’s margina…lisation and the accretion of executive power. For UK in a Changing Europe’s report on the constitutional landscape, we show how – in the legislative process and control of public money and executive action, including delegated legislation.

What role does the UK Parliament play in sanctioning an individual? [Video]

Sanctions are imposed on an individual in two stages - by Ministers first making regulations and secondly designating th…e individual, using a power in those regulations. Parliament has a role in the first stage, but not the second.

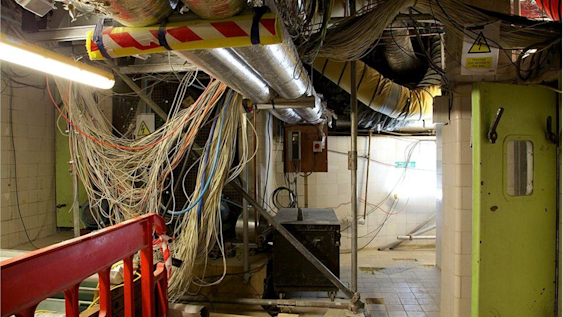

Written evidence to the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee: the Restorat…ion and Renewal of Parliament

Our submission to the Public Accounts Committee highlighted the financial and practical challenges that MPs face in deci…ding the fate of Parliament’s Restoration and Renewal programme. We particularly questioned the viability of the proposal to continue operating the House of Commons Chamber in the middle of a building site.

Written evidence to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee: Retained E…U Law: Where next?

Our submission to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee inquiry into retained EU law (REUL) placed the issue…in the context of our Delegated Legislation Review. It discussed REUL’s diversity and amendment; the people and organisations to whom REUL amendment may matter; and parliamentary scrutiny of delegated legislation arising from amending REUL.