In its recent landmark report, the House of Commons Liaison Committee recommended a widening of the circle of those that select committees should hold to account, and a turn towards the public in all committee activity, but also tighter links between select committees and the House of Commons Chamber.

As part of the celebrations it sponsored to mark the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the departmentally-related select committee system in June 1979, the House of Commons Liaison Committee (the committee which comprises the Chairs of all the other select committees) conducted an inquiry in the first part of this year into the influence and effectiveness of select committees. It did not manage to agree its report before the summer but, at an hastily convened meeting on 9 September, it managed to squeeze its report out before the possibility of a dissolution of Parliament triggered by the vote due to be held that evening on an early general election, under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act.

The report is now available on the Liaison Committee’s website. In contrast to its exhortation to other committees to produce shorter reports with fewer recommendations, it is lengthy (304 paragraphs) and recommendation-heavy (listing 84 conclusions and recommendations). Indeed, the summary alone is of the kind of length they seem to think other committees should be aiming for.

The Committee might be forgiven for this do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do approach on the grounds that it rarely produces a report of its own. Their last large-scale look at the effectiveness of the committee system was published seven years ago, in 2012.

The select committee system: a reform history

The lineage of this latest weighty volume can be traced back to the Shifting the Balance series of reports around the turn of the century, in which the-then Liaison Committee took on the government in a concentrated attempt to strengthen the powers of select committees. There was a good deal of to-ing and fro-ing between the Committee and the government over its radical recommendations, most of which were rejected.

But subsequently there was a confluence of events which triggered change, namely:

- the publication in 2001 of the report of the Hansard Society Commission on Parliamentary Scrutiny, chaired by Lord (Tony) Newton, a former Conservative Leader of the House; and

- the almost-simultaneous arrival in that very post of Robin Cook, who had resigned as Foreign Secretary over the Government’s policy towards Iraq and who was determined to be a reforming Leader (a relatively rare bird), using his chairmanship of the Modernisation Committee as his vehicle.

The upshot was the implementation of a number of the reforms proposed by the Newton Commission and the Liaison Committee, and a very substantial increase in the resources allocated to support the select committees.

‘Core tasks’ revision

One of the key recommendations of the Newton Commission, supported by the Modernisation Committee and endorsed by the House in 2002, was the creation of ‘core tasks’ for the departmental select committees. These were first formulated by the Liaison Committee in 2002 and revised in 2012 (pre-appointment hearings for certain major public offices having been added – after long pressure from the Liaison Committee – in 2007 as part of then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s ‘Governance of Britain’ initiative).

The Liaison Committee’s new report devotes its first chapter principally to these tasks, and ends by providing a fairly radical revision of the list. It emphasises the ‘how’ as much as the ‘what’ of what committees should be expected to do, and this theme runs throughout the rest of the report.

Part of the intended purpose of the core tasks was to make the select committees more accountable to the House as a whole for the tasks it had delegated to them, and the new report builds on this idea with some further proposals – including the revival of the practice of committees producing an annual report on their activities, which had fallen away after 2015.

Increased committee accountability to the House

The report also recommends that whole-House elections should be extended to all scrutiny committee chairs, and goes on to suggest that those elected Chairs should have their own question time in the Chamber, and account for the ways in which they and their committees have carried out the duties delegated to them by the House.

This accountability extends to the behaviour of Members and the responsibility of Chairs – as holders of leadership roles – actively to “promote and robustly support” both the seven principles of public life and the House’s newly established behaviour code [PDF], noting that they must be willing to challenge poor behaviour wherever it occurs.

The Committee emphasises, however, that the revised annual accountability reports should be directed towards the public, not just the professionals within Westminster and Whitehall. It envisages that they should be “engaging” documents, making use of infographics or even video to tell each committee’s story.

Wider stakeholder engagement

These suggestions are of a piece with many other recommendations which place emphasis on engagement as a key duty of the committees. They are encouraged to build on existing best practice in involving a much wider range of “stakeholders” in every stage of their inquiries, including the planning of their work programmes, through their evidence-taking and right up to their report launch (where the Committee recommends removing the time limit on the circulation of advance copies to give civil society a better chance to get behind recommendations on publication).

This emphasis on broadening the church of those who are heard during, and involved in, committee inquiries is the report’s most dominant theme. The “research community” (publicly and charitably funded, and distinct from the think-tanks, trades unions, trade associations and lobbying charities with specific agendas to promote) is strongly encouraged to find ways of feeding its work into the committees’ deliberations.

In turn, the committees are enjoined to work more strategically – an approach advocated by the Hansard Society as long ago as 2011 – and at a more measured pace that would allow such engagement to flourish. There is even a quiet proposal, tucked away in paragraph 168, for the establishment of an “Office of Public Evidence” to support not just the committees but the wider public to gain access to objective and impartial assessments of the facts of national life.

Two ongoing issues

The report considers two current problems at length, but without coming to any very definite conclusions.

Post-Brexit demands

The whole of chapter 3 is devoted to the role of committees in a putative post-Brexit world. The main message is that they will be needed more than ever to scrutinise the wider range of policy areas for which Parliament will become responsible (for example, agriculture, fisheries, energy, environment, medicines regulation), and more immediately to get a grip on the huge range of international trade and other negotiations (not least with the EU) which may be taking place over the next decade or so. The Committee enjoin flexibility of resourcing, and gently warn that more, rather than fewer, resources are likely to be needed to support this work.

Committee powers

On the question of the powers of committees to compel witnesses to attend, brought to a head by the recent stand-off between the DCMS and Privileges Committees and the Prime Minister’s current principal policy adviser, the Liaison Committee avoid pre-empting the findings of the Privileges Committee in its wider inquiry into penal powers but conclude that the present situation, in which the committees appear to have untrammelled powers but have no means of enforcing them in the face of disobedience, is no longer tenable.

Formalising committees’ greater accountability reach

Where the Liaison Committee is more forthright is in recognising the increasing role of select committees in considering matters of public concern where there is a need for accountability to the public through Parliament. Its proposed core tasks include holding to account the actions of organisations or individuals with significant power over the lives of citizens or with wide-reaching public responsibilities, and it recommends Standing Order changes to recognise and regularise the fact that that committees already interpret their role in this way.

Tighter links into Chamber business

As well as better engagement and accountability to the public, the report seeks to strengthen the relationship between committees and the House of Commons Chamber. In paragraph 46 of the report, the Committee touches briefly on the academic political science distinction between ‘talking’ and ‘working’ Parliaments – broadly, that between plenary-based and committee-based legislatures.

The report concludes that the House of Commons may not yet have fully come to terms with the shift, over the last 40 years, in the balance between its plenary and its committees in discharging its fundamental task of holding the government to account. The Committee suggests that the time may have come:

“to take a long and comprehensive look at the ways in which the select committees reinforce rather than compete with the work of the plenary, and … to make recommendations which would represent a step change in that settlement”.

That is one side of the story – the more technical role of select committees as the organs of parliamentary accountability.

But the report concludes that the committees:

“face both inwards to Westminster and Whitehall and outwards to the public — they are a bridge or a conduit between the two. As such they are as much part of that ill-defined organism known as ‘civil society’ as they are a part of Parliament. Much of what we have had to say in this report has been celebrating the success of the select committees in reaching out to and engaging with the world outside Westminster. We hope they will continue to act as enablers who make government accountable not just to small groups of elected representatives but to all those parts of our society who want to hold their temporary rulers to account”.

Paul Evans was one of the editors of, co-authored an article in, and contributed the Conclusion to, the special issue of the Hansard Society’s journal Parliamentary Affairs on ‘40 years of departmental select committees in the House of Commons’ (vol 72, issue 4, October 2019).

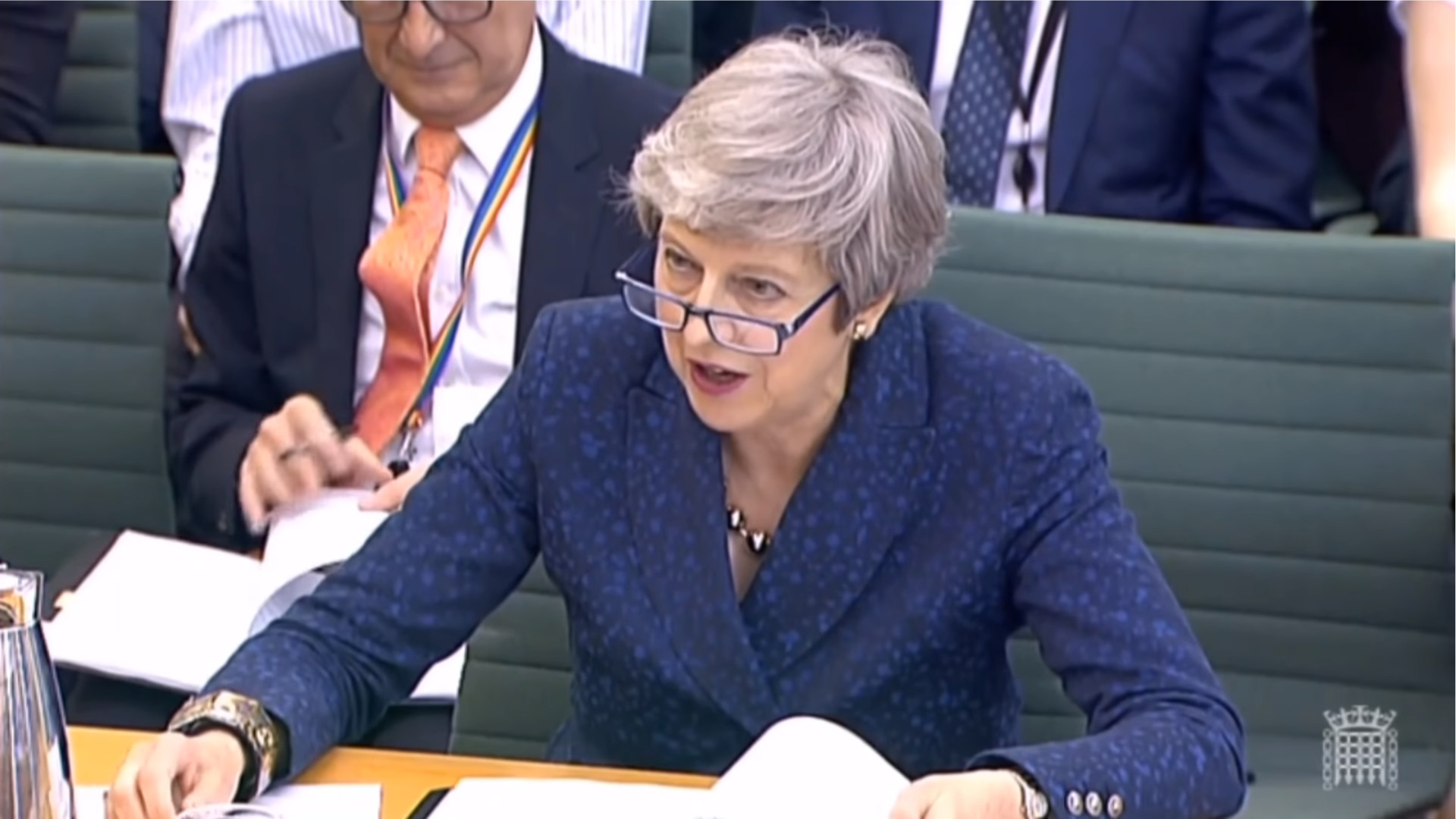

Banner image: ParliamentLive.TV, UK Parliament

Enjoy reading this? Please consider sharing it

Latest

Compendium of Legislative Standards for Delegating Powers in Primary Legislation

The scope and design of the delegation of legislative powers in any Bill affects the long-term balance of power between…Parliament and Government. The House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC) scrutinises all such delegation. This report distils standards for the delegation of powers from 101 DPRRC reports from 2017 to 2021.

Genetically modified organisms: Primary or delegated legislation?

A Statutory Instrument comes into force on 11 April that changes the legal requirements for the release of certain types… of genetically modified plants. Some argue that the changes should have been made by primary, rather than delegated, legislation. Where does the boundary between the two lie?

Constitution and Governance in the UK: Parliament and Legislation

The Brexit process, the pandemic and the approach of the Johnson Government have all tended towards Parliament’s margina…lisation and the accretion of executive power. For UK in a Changing Europe’s report on the constitutional landscape, we show how – in the legislative process and control of public money and executive action, including delegated legislation.

What role does the UK Parliament play in sanctioning an individual? [Video]

Sanctions are imposed on an individual in two stages - by Ministers first making regulations and secondly designating th…e individual, using a power in those regulations. Parliament has a role in the first stage, but not the second.

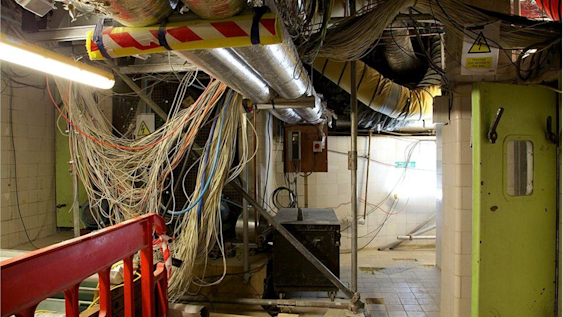

Written evidence to the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee: the Restorat…ion and Renewal of Parliament

Our submission to the Public Accounts Committee highlighted the financial and practical challenges that MPs face in deci…ding the fate of Parliament’s Restoration and Renewal programme. We particularly questioned the viability of the proposal to continue operating the House of Commons Chamber in the middle of a building site.

Written evidence to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee: Retained E…U Law: Where next?

Our submission to the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee inquiry into retained EU law (REUL) placed the issue…in the context of our Delegated Legislation Review. It discussed REUL’s diversity and amendment; the people and organisations to whom REUL amendment may matter; and parliamentary scrutiny of delegated legislation arising from amending REUL.